Hepatitis B virus in Lao Blood donors: a nationwide serostudy

Testing for HBsAg by rapid test

Project coordinators: Phonethipsavanh Nouanthong

Partners: Lao Red Cross, Luxembourg Institute of Health

Background

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major global public health problem. Chronic HBV infection causes severe liver damage and 25% of patients die later from related chronic active hepatitis, cirrhosis, or primary hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Mother-to-child transmission is generally the most common transmission route in South East Asia. The risk of developing chronic hepatitis B is highest with 90% if infected at birth and decreases to 5-10% if infection occurs in adulthood. Highly endemic countries have chronic HBV infection rates between 8-20%, e.g. parts of South East Asia, tropical Africa and parts of China. In these regions, the burden of HBV-related HCC and hospitalization are dramatically high in later stages of life. Hepatitis B vaccination was introduced in Lao PDR as a three dose course in combination with Diphtheria-Tetanus- Pertussis in 2001. An additional birth dose followed in 2003/2004. Since 2009, the pentavalent diphtheriatetanus- pertussis-hepatitis B-Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine (DTPw-HepB-Hib) has been used.

In 2018, the estimated coverage for the 3rd dose of DTPw- HepB-Hib was 84%, while the birth dose coverage was only 55%.

In 2018, the WHO estimated that the age-standardized incidence of liver cancer in Lao PDR was 22.4 per 100 000 population, ranked 5th highest worldwide. More than 40% of the adult Lao population, born before the introduction of the vaccine, are likely to have been exposed to the virus. Despite representing a substantial public health burden, the epidemiology of hepatitis B in Lao PDR is not well understood. The lack of HBV surveillance and limited access to testing impede efforts to assess HBV treatment and disease burden in the whole country. In recent years, studies investigated the prevalence of chronic infection among mothers and their children as well as protection levels conferred through vaccination. However, these studies varied greatly in design and laboratory methods which complicates the interpretation of the findings. In addition, studies focusing solely on women may underestimate the HBV prevalence in Lao PDR as the chronic infection rate is known to be lower than in men.

In Lao PDR, more than 30 000 blood units are used for transfusion every year (Dr. Chantala Souksakhone, Director of National Blood Transfusion Center, personal communication, 2018). The high endemicity of HBV increases the relative risk of transfusion transmitted infection (TTI). The WHO recommends a mandatory pre-transfusion blood screening for HBV, Hepatitis C Virus (HCV), Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), and Syphilis in all countries. In the early 1970s, the Lao National Blood Centre (NBC) introduced a routine screening for HBV infection. Blood donors positive for the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) are informed of their HBV infection status, counselled and advised not to return for blood donation (Dr. Chantala Souksakhone, personal communication, 2018). However, due to challenges with donor counselling and maintenance of donor records, some HBsAg positive donors still return for blood donation afterwards. Furthermore, due to limited resources, the blood is currently screened only for HBsAg, but not for antibodies against HBV.

In this study, we investigated a large cohort of Lao first time and repeat blood donors enrolled at eight different blood donation sites nationwide for markers of HBV infection in order to determine regional, occupational and age or sex related differences.

Methods

Participants

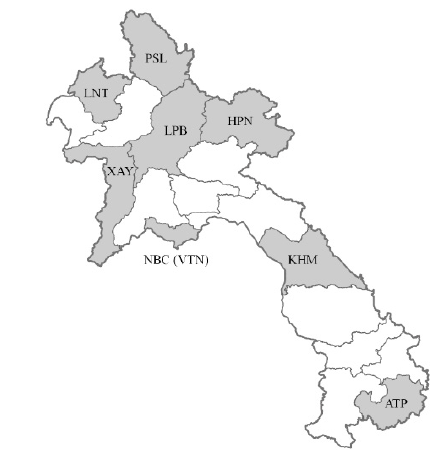

From November 2013 to May 2015, we recruited 5017 voluntary blood donors from 8 different blood centers: the NBC in Vientiane Capital in Central Lao PDR, Khammouane (KHM) and Attapeu (ATP) in the South, and Luang Prabang (LPB), Luang Namtha (LNT), Phongsaly (PSL), Huaphan (HPN) and Xaiyabuly (XAY) in the North (Figure 1).

Blood donor eligibility was assessed according to the standards of the National Blood Transfusion Service and included the history of blood donations. The donors were informed about the study and all people willing to take part were included. Written informed consent was obtained prior to data and sample collection. The study was approved by the Lao National Ethics Committee for Health Research (reference NECHR 059/2013 and 059/2014).

Figure 1. Map of Lao PDR. Provinces included in this study are highlighted in dark grey. PSL = Phongsaly, LNT = Luang Namtha, HPN = Huaphan, LPB = Luang Prabang, XAY = Xayabouli, NBC = National Blood Center in Vientiane (VTN), KHM = Khammouane, ATP = Attapeu. The map was created with QGIS (QGIS Development Team, 2018) using the world borders dataset (http:// thematicmapping.org/downloads/world_borders.php, 2019). The data regarding the administrative boundaries of Lao PDR was obtained from the Humanitarian Data Exchange website (https://data.humdata.org/dataset/ lao-admin-boundaries, the dataset provided by the National Geographic Department of Lao PDR, 2019). The projection used: EPSG 4326 – WGS 84.

Sample and data collection

After informed consent, 5 ml of blood were collected at the time of blood donation. Samples collected by either fixed or mobile units of NBC were shipped to Institut Pasteur du Laos (IPL) for serum separation and storage. At the provincial level, the samples were processed at the study site. The serum was frozen at -20ºC and shipped to IPL every three months. All serum samples were stored at -80ºC at IPL until analysis. The demographic data of donors were collected, including age, sex and occupation, as well as a number of donations, date and location of blood donation.

Laboratory analyses

Commercial ELISA kits (Diasorin, Italy) were used to detect anti-HBc and anti-HBs antibodies. Anti- HBc positive samples that were negative for anti-HBs antibodies or with unknown anti-HBs status, were tested for HBsAg (Diasorin, Italy). Anti-HBc negative samples were considered to be negative for HBsAg. For the purpose of this study, HBsAg positivity was interpreted as representing chronic infection. Anti-HBc positive results indicated previous exposure to the virus, whereas anti-HBs positive results were indicative of immune protection following infection (in the presence of anti-HBc antibodies) or vaccination (anti-HBs alone). According to the manufacturer’s instruction, a titer ≥ 10 IU/L was considered as reactive for anti-HBs. Samples with an OD value within the +/- 10% range of the OD value of the cut-off calibrator were considered as “equivocal” for anti-HBs.

Data analyses

Data analyses were conducted using R statistical software with the following packages: “tidyverse”, “MASS”, “car”, “lmtest” and “epitools”. For first-time donors, bivariate and logistic regression analyses were performed in order to investigate associations with HBsAg and anti-HBc positive status. In bivariate analyses, odds ratio, 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p values were calculated for seropositive participants. Binary regressions were performed using a stepwise method for removing variables that were not associated with the response variable one by one, taking both the p-value of the variable and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) of the model into consideration. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. A correlation value >0.5 or a variance inflation factor >5 was considered as correlation and the decision to exclude the variable was made on a case-by-case basis: the variable which was deemed to be less important and/or with the lower impact was removed. The significance of the final model in comparison with the null model was tested using a likelihood ratio test (R function “Anova” with argument test set to “Chisq”). In addition, the individual effect of the variables in the model was tested by Wald tests (R function “Anova” with argument test. statistics set to “Wald”).

Results

Participant characteristics

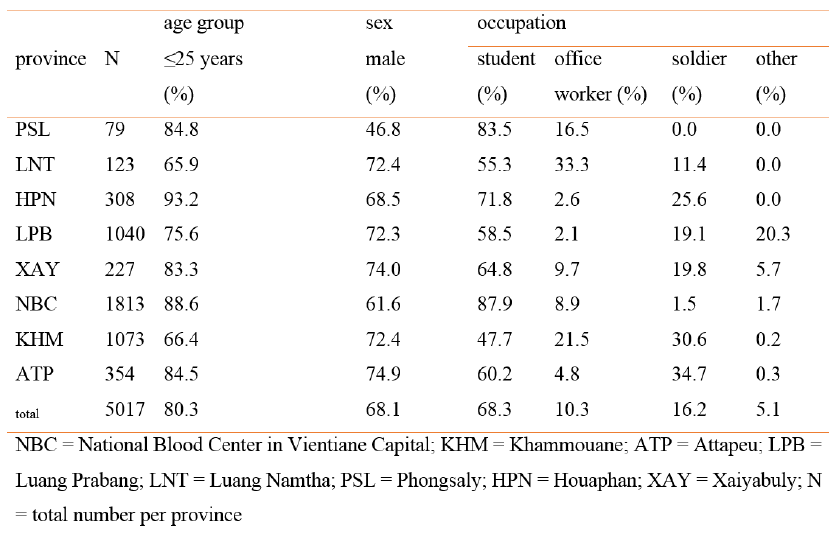

From the 5017 participants included, the majority were male (68.1%), students (68.3%) and younger than 25 years of age (80.3%, mean age = 22.2 years, ranging from 16 to 65 years) (Table 1). Information regarding the frequency of blood donations was available for all but 5 participants. More than half of the 5012 participants were first-time donors (55.8%), 21.1% gave blood for the second time and all others more than two times (ranging from 3 to 35 times).

Table 1. Participant characteristics by province

Serological profiles of HBV markers

Overall serological profiles

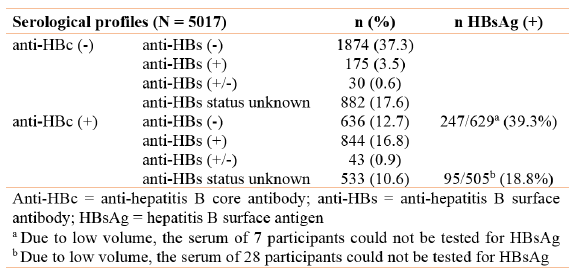

All 5017 samples were tested for anti-HBc antibodies and 2056 (41%) were positive (Table 2). Due to limited serum volume and financial resources and because the focus of the study was on anti-HBc and HBsAg prevalence, only 3602 participants were in addition tested for the presence of anti-HBs antibodies. 21.8% were found to be positive for anti-HBs and 73 (1.5%) participants had an equivocal result. Only 3.5% of the 3602 participants were anti- HBs positive and anti-HBc negative, indicating previous vaccination. 636 participants were anti-HBc positive and anti-HBs negative, and from those, 247 were HBsAg positive (4.9% of the total). For 533 anti-HBc positive participants, the anti-HBs status was unknown and 95 of them were HBsAg positive. Due to low volumes of the serum samples, 35 (3%) could not be tested for HBsAg (Table 2). Overall, 342 of the 1134 participants tested were positive for HBsAg. For this study, we considered all anti-HBc negative samples as well as anti-HBc positive and anti-HBs positive or equivocal samples as negative for HBsAg.

Table 2. Serological profiles of the participants

Serological profiles by participant characteristics

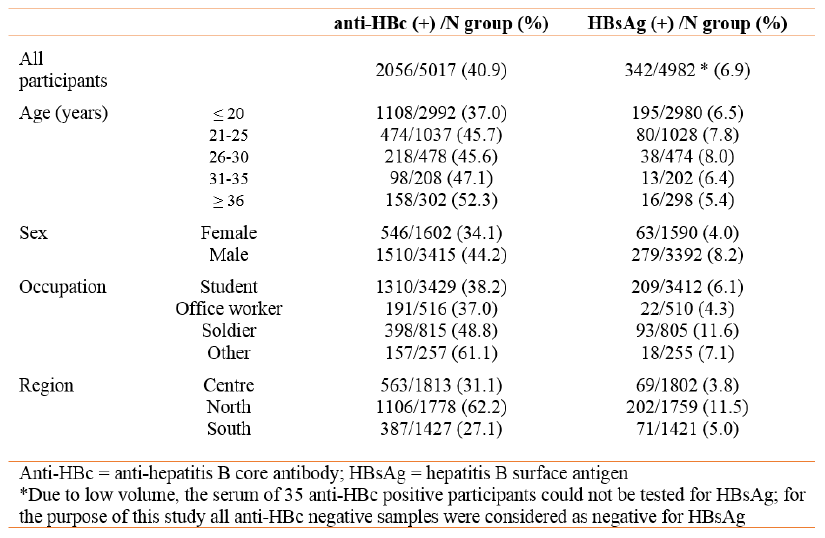

The proportion of anti-HBc positives was higher in male donors, in participants ≥36 years and in participants from the Northern provinces (Table 3). Male participants, donors from Northern provinces and soldiers showed a higher prevalence of chronic infection.

Table 3. Serological profiles according to participant characteristics

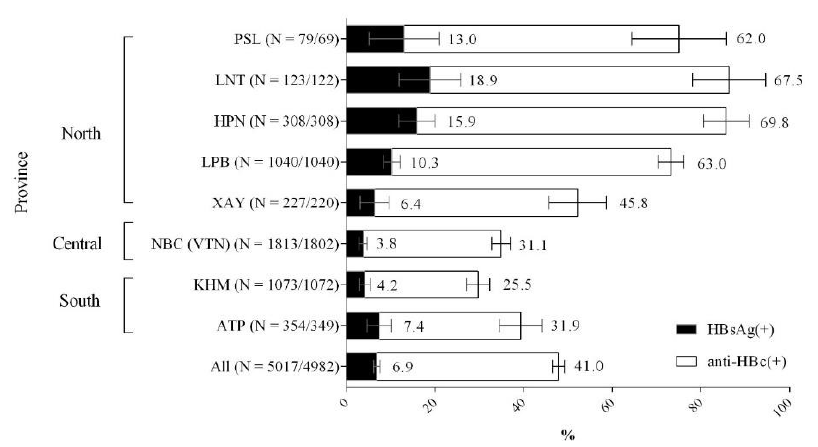

The prevalence of anti-HBc antibodies and HBsAg varied strongly by geographic location (Figure 2). Participants from provinces located in the North of Lao PDR seemed to be disproportionally affected by HBV infection with an anti-HBc seropositivity of 62.2% and HBsAg prevalence of 11.5% as compared to 27.1% and 5.0% respectively in the South of Lao PDR. The lowest rate of anti-HBc positivity was found in Khammouane province (25.5%) while the highest rate was observed in participants from Huaphan province (69.8%). The highest rate of chronic infection was observed in Luang Namtha (18.9%).

Figure 2. Anti-HBc and HBsAg prevalence by province. PSL = Phongsaly, LNT = Luang Namtha, HPN = Huaphan, LPB = Luang Prabang, XAY = Xayabouli, NBC = National Blood Centre in Vientiane (VTN), KHM = Khammouane, ATP = Attapeu. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval. Numbers beside the error bars indicate the percentage per province. Numbers in brackets indicate the number of participants tested for anti-HBc and the total numbers taken into account for calculating the HBsAg prevalence. Due to low serum volumes, not all anti-HBc positive samples could be tested for HBsAg.

Serological profiles of first-time donors compared to repeat donors

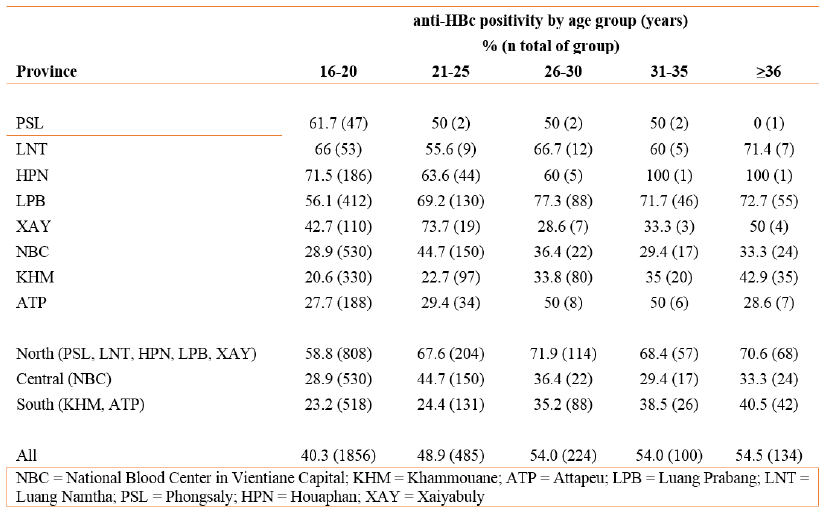

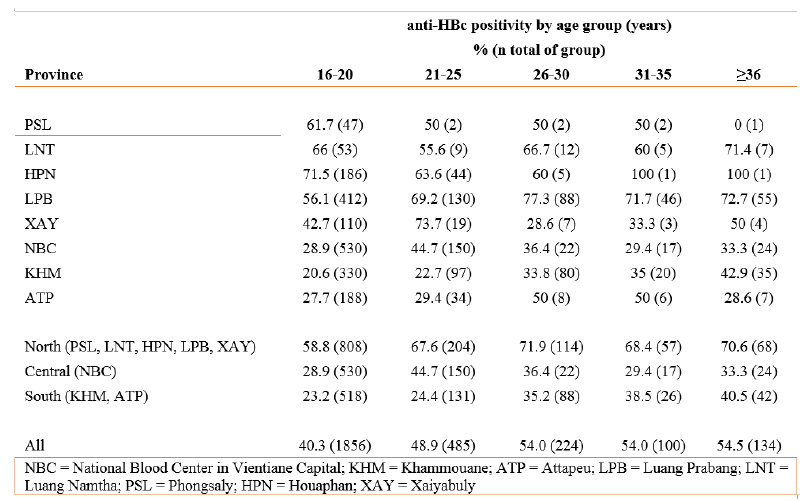

From the 5012 participants with information regarding the frequency of their blood donations, 55.8% were first-time donors. All 2799 first-time donors were tested for anti-HBc, but due to low sample volumes, only 2778 were tested for HBsAg. The overall anti-HBc prevalence was significantly higher in first-time donors than in repeat donors (44.1% vs. 37%; p<0.001). Anti-HBc seropositivity in first-time donors also varied by province (Table 4). The prevalence of anti-HBc was higher in the Northern provinces compared to the other provinces irrespective of the age group.

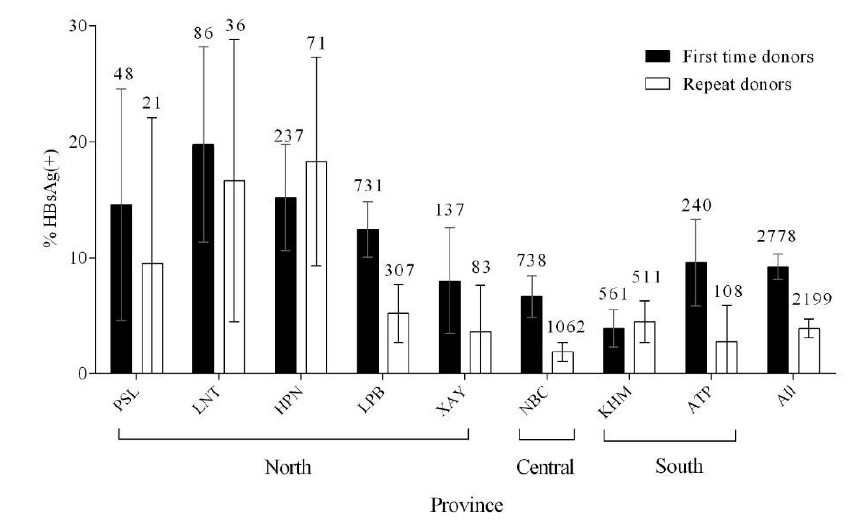

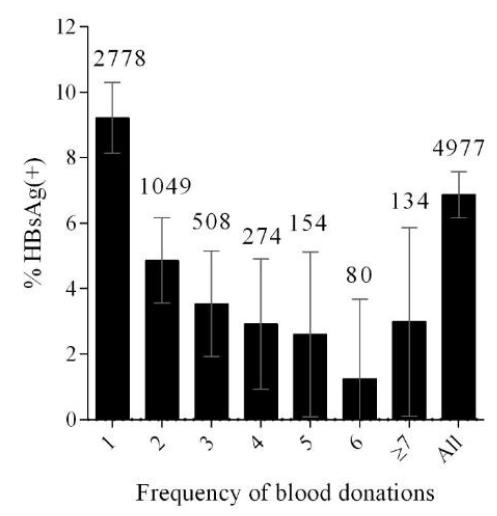

Likewise, the prevalence of HBsAg was significantly higher in first-time donors than in repeat donors (9.2 vs. 3.9; p<0.001) and HBsAg prevalence varied by province (Figure 3). The prevalence of HBsAg in first-time donors was higher in the Northern provinces (13.1%) compared to Central and Southern provinces (6.6% and 5.6% respectively). The prevalence of HBsAg declined with increasing numbers of blood donations (Figure 4).

Table 4. Anti-HBc seropositivity by province and age group in first-time blood donors (N = 2799)

Figure 3. HBsAg prevalence in first-time and repeat donors by province. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval. Numbers above the error bars indicate the total numbers considered. PSL = Phongsaly, LNT = Luang Namtha, HPN = Huaphan, LPB = Luang Prabang, XAY = Xayabouli, NBC = National Blood Centre in Vientiane, KHM = Khammouane, ATP = Attapeu. Information on the frequency of blood donation was not available for 5 individuals.

Figure 4. Prevalence of HBsAg by the number of blood donations, including the current donation at the time of sample collection. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval. Numbers above the error bars indicate the total numbers considered. Information on the frequency of blood donation was not available for 5 individuals.

Factors associated with HBsAg positivity in first-time donors

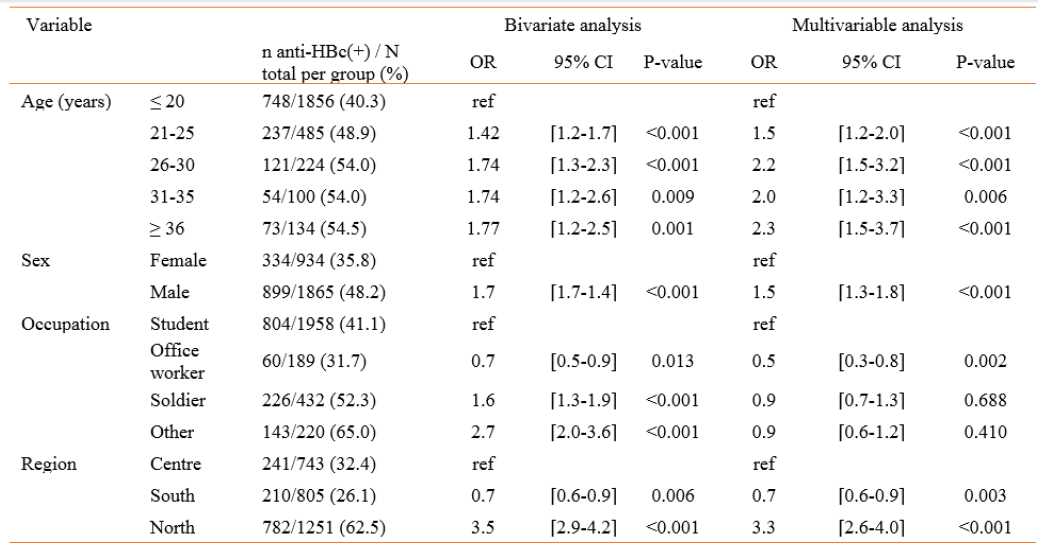

After bivariate analysis, all variables were included in the logistic regression model to evaluate the relative contribution of each factor on being seropositive for HBsAg. Three variables remained independently associated with being seropositive for HBsAg. Male participants, soldiers and participants from Northern provinces were significantly more likely to be positive for HBsAg (Table 5).

Table 5. Risk factor analysis for HBsAg seroprevalence among first-time donors (N = 2778)

Factors associated with anti-HBc positivity in first-time donors

In bivariate analysis, all four variables (sex, age, occupation and recruitment site) were significantly associated with anti-HBc positivity and therefore included in the logistic regression model (Table 6). All variables remained independently associated with being seropositive for anti-HBc. Participants of at least 36 years, males and participants from the North were 2.3, 1.5 and 3.3 times more likely to be positive for anti-HBc compared to participants under 20 years of age, females and participants from Central provinces. In contrast to factors associated with HBsAg positivity, soldiers were not more likely to have been previously exposed to HBV.

Table 6. Risk factor analysis for anti-HBc seroprevalence among first-time donors (N = 2799)

Discussion

In this study, regional, occupation, age and sex-related differences in HBV epidemiology in Lao blood donors were investigated. The seroprevalence of HBsAg extrapolated to 4982 participants was 6.9%, and was 9.2% in first-time donors after excluding repeat donors who showed a much lower proportion of HBsAg positivity (3.9%). This finding is comparable with earlier studies that found an HBsAg prevalence of 8.7% and 9.6% in first-time blood donors. In addition, 41% of the participants were positive for anti-HBc, indicating that they had been in contact with the virus at some point during their lives. Virtually all of the donors (>99%) were born before the introduction of HBV vaccination in Lao PDR in 2001, explaining the low seroprevalence (3.5%) of anti-HBs alone profile. Since HBsAg testing was only conducted for anti-HBc positive and anti-HBs negative samples or with unknown anti-HBs status, we cannot exclude that we missed HBsAg positive samples due to false anti-HBs positives or anti-HBc negatives. For the purpose of this study, anti-HBc negative samples were considered negative for HBsAg. These samples were not tested for HBsAg, as only acute infected participants or donors with low infectivity might show this serological profile. Strikingly, the rate of exposure and current infection was much higher in Northern provinces than in the Centre or South of Lao PDR, irrespective of the age group. Such regional variation has not been described before and according to our knowledge, no information about prevalence rates in neighboring regions of the Northern provinces is available. The observed differences could relate to local variations in risk practices such as for example tattooing, piercings, birth practices and sexual exposure. Indeed, the Khmou, an ethnic group living in the North of Lao PDR, has previously been linked to increased vulnerability to prostitution and increased risk for exposure to HIV or other sexually transmitted diseases. Development work in border areas, such as the improvement of route 3, linking Lao PDR to Thailand and China, has impacted the economic landscape in the Upper Mekong region. Among others, increased prevalence of HIV and rising numbers of small road side shops, offering often alcoholic beverages and eventually sexual services, have been cited as negative consequences of this economic shift. It has also been reported in other settings that the HBV and hepatitis C prevalence in indigenous populations and ethnic minorities may be high or different than in the general population. Followup studies are therefore clearly warranted and should capture potential risk factors as well as ethnicity.

Similar to previous studies, HBsAg and anti-HBc prevalence rates were higher in males than in females, both in first-time donors and in the overall cohort. This finding should be considered when designing future studies regarding disease burden and exposure. In comparison to the youngest age group, older participants were more likely to have had an infection with HBV in the past but age did not seem to play a role in the model for being a chronic carrier. This is likely explained by infections at an early age often resulting in chronic infection, whereas infections during adulthood are much less likely to do so. The positive association between age and anti-HBc seropositivity may reflect continuous exposure to hepatitis B infection in an endemic country.

In comparison to students, soldiers were more likely to be chronic carriers but they were not more likely to have had an HBV exposure. Since the high rate of HBsAg positivity indicates early life exposure, it may be hypothesized that soldiers originate more often from less wealthy families with a higher likelihood of HBV exposure than students.

Even though the rate of HBsAg positivity was significantly higher in first-time donors than in repeat donors, the fact that HBsAg positive donors return for blood donation is of concern. There are several possible explanations for this. Firstly, the detection methods used at the Lao Red Cross may not be sensitive enough to detect low levels of HBsAg. This possibility has obvious implications for blood safety and methods for the screening of blood donations should be reviewed. However, it would probably only explain a small proportion of the positive repeat donors. A second possible reason why the repeat donor HBsAg prevalence is high could be that the blood donor database may not be robust enough to prevent repeat HBsAg positive donations.

In another investigation, we have found significant problems with donor identification across multiple blood donation sites and counseling (manuscript in preparation). Lastly, a small number of repeat donors who are HBsAg positive may have become positive through infection since the previous donation. In Houaphan, the prevalence of HBsAg was higher in repeat donors than in first-time donors for unknown reasons, which should be further investigated. The higher prevalence of HBsAg in participants who donated more than 7 times compared to 4 to 6 times can be explained by low overall numbers for each blood donation group.

Serum samples obtained from blood donors may serve as a representative sample of the general adult population in Lao PDR and have several advantages: they are relatively easy to obtain, there are multiple blood donation sites all over the country and several age groups, as well as samples from both sexes, are available. However, the sex ratio in our study was not matched to the general adult Lao population, and the inclusion of a high proportion of males may have resulted in an overestimation of HBV exposure and chronicity. A limitation of this study was that, due to resource-limitations and low serum volume, not all samples could be tested for anti-HBs. However, since basically all participants were born before vaccine introduction, we do not expect the percentage of donors with post-vaccination serological profile to be much higher than among the tested participants.

In conclusion, our study confirmed an overall high HBsAg and anti-HBc prevalence in Lao PDR, albeit with considerable regional variation, the reasons for which need further clarification. Vaccination coverage including the birth dose needs to be strengthened to reduce the rate of chronic carriers in the next generation. The identification of a sizeable number of HBsAg positives among repeat donors warrants a thorough investigation of current blood screening, record keeping, donor identification and counseling practices.

These findings have been presented and discussed with the Lao Red Cross and have been formatted as a manuscript for publication