Timeliness of immunisation with Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis whole cell–Hepatitis B–Haemophilus influenzae Type B at different levels of the health care system in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic: a cross sectional study

Record keeping in the district hospital, Lao PDR

Project coordinators: Lisa Hefele (LIH)

Partners: Luxembourg Institute of Health, Lao Tropical and Public Health Institute, Lux Dev

Background

The timely administration of vaccines is considered to be important for both individual and community immunity. Studies in the UK, China, the USA and lower income countries such as Senegal, Malawi and India have investigated the impact of timeliness on vaccination.

Delayed vaccinations of children may increase the risk of infection before vaccination, compromising the success of the intervention as well as herd immunity.

On the other hand, vaccinations are given too early or without sufficient interval between the doses may not be fully protective.

In Lao PDR, the expanded program on immunization (EPI) is one of the most successful public health programs and routine vaccination coverage has increased for more than ten years. In 2018, the estimated coverage for the 3rd dose of the pentavalent diphtheria-tetanus- pertussis-hepatitis B-Haemophilus influenza type b vaccine (DTPw-HepB-Hib) was 84%(“Gavi country factsheet: Lao People’s Democratic Republic,” n.d.). However, it was reported in 2012 that only a small number of children had received all 3 doses of the DTPw- HepB-Hib vaccine by the recommended age of 4 months.

In Lao PDR, Central hospitals (CH) in Vientiane Capital represent the highest level of the health care system, followed by provincial hospitals (PH) and district hospitals (DH). Health centers (HC) that provide only basic medical services represent the lowest level. Typically, health care facilities (HCF) such as HC or DH provide immunization services to several villages within a flexible radius. Vaccinations are registered in the yellow child vaccination card (YC), which stays with the family, and the hospital records (HR), which can consist of one registry book at the mother and child department but also includes the vaccination books of the EPI team, typically one vaccination book for each village. Regardless of where the vaccination takes place, the children are usually listed in the book of the home village and in case of outreach vaccination, the books are taken to the villages. The HR as well as YCs are standardized and provided by the health offices.

The primary objective of this study was to investigate the timeliness of vaccination with the three doses of the pentavalent DTPw-HepB-Hib routine childhood vaccine in fully vaccinated children in Bolikhamxay province and Vientiane Capital. For this purpose, the dates of vaccination as recorded in the YC and HR were compared and the proportion of children that received the vaccination with delay was estimated. Furthermore, we investigated risk factors associated with delayed vaccination.

Participants and Methods

Participants

The study took place in the context of a larger vaccine immunogenicity study in Bolikhamxay province and in the Vientiane capital in 2017. All participants had received the full course of the DTPw-HepB-Hib vaccine, documented in either the HR or YC. In Vientiane Capital, 319 children aged 8 to 23 months and their parents/guardians who visited the Children´s Hospital for unrelated health reasons or MR vaccination were enrolled. In Bolikhamxay province, 843 children aged 8 to 28 months were recruited, who were vaccinated in the PH, three DHs and ten HCs. Before the start of the sample collection, the study was explained to the head of the participating village and to the parents of the participants by a health care worker. All parents/ guardians signed the informed consent form and could withdraw their participation at any time. A standardized questionnaire was designed to collect information about the participant´s socio-economic background, access to health care, history and location of vaccination. Vaccination histories were verified and confirmed in the HR at the HCF, if available, as well as on the YC. The data were double entered into Epidata independently before data analysis. Serum samples were collected from participating children to assess antibody levels. The study was approved by the Lao National Ethics Committee (Reference numbers 033/2017/NECHR, 032/2017/ NECHR, 031/2017/NECHR, 056/2017/NECHR) and by the internal ethics review board of the Institut Pasteur du Laos.

Vaccination dates

The vaccination history of the participants was recorded from the HR and/or YC. The age of the participants in weeks at the time of the vaccination with DTPw-HepBHib and with the hepatitis B birth dose was calculated based on the birthdate and the date of the vaccination. The age when receiving each vaccine dose was defined as “timely” when between 6-7 weeks for dose 1 (DTPw- HepB-Hib 1), 10-11 weeks for dose 2 (DTPw-HepB-Hib 2) and 14-15 weeks for dose 3 (DTPw-HepB-Hib 3). When the participant was older or younger, the vaccination was considered to be “earlier” or “later” than recommended. An interval of 4 weeks is recommended between each dose and intervals shorter than 4 weeks or longer than 5 weeks were considered “shorter” or “longer” than recommended. The WHO recommends that primary vaccination with the DTP-containing vaccine is completed at 14 weeks and at latest at 6 months (24 weeks) of age. In this study, we considered 16 weeks (in order to give some time margin) and 24 weeks (the latest WHO recommendation for completeness) as cut-off for the timely completion of vaccination with DTPw-HepB-Hib. The proportion of participants that had received DTPw- HepB-Hib by 16 and 24 weeks at each health care level was compared to the level of the CH. Furthermore, we used 24 weeks as a cut-off in order to identify factors associated with the timely completion of the schedule or not.

In order to detect irregularities in the vaccination documents of participants who had both the HR and YC available, the time discrepancy between documented vaccination dates was obtained by subtracting the vaccination date in the YC from the vaccination date in the HR. Since vaccination dates in the YC were considered more reliable as the cards stay with the mothers, we gave priority to the YC to calculate the median age at vaccination and the intervals between vaccinations. Whenever the YC was not available, the date in the HR was used.

Laboratory analysis

The serum samples were analyzed by commercial ELISA kits as described elsewhere (Hefele et al, 2019) Protective immunity was considered if the participants had an antidiphtheria titer ≥0.1 IU/ml, an anti-tetanus titer >0.5 IU/ ml and an anti-Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) titer >1.0μg/ml. For the anti-hepatitis B titer (anti-HBs), two cut-offs were used: ≥10 IU/l and ≥100 IU/L. A titer ≥22 U/ml was used as an indication of exposure to the vaccine antigen for B. pertussis.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were conducted using R software (version 3.5.3) with the following packages: “tidyverse”, “lubridate”, “MASS”, “rcompanion”, “lmtest”, “car”, “epitools” and “pROC”. Chi-squared, Fisher´s exact test and independent student t-test were used as appropriate. In order to assess whether any of the socio-demographic or vaccination related factors are associated with the completion of primary vaccination with DTPw-HepB-Hib by 24 weeks (6 months) of age, Chi‐square test and Fisher’s exact test were performed. Odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p-value were calculated. Logistic regression with binomial response variable was performed in order to determine which factors affect the completion of vaccination by 24 weeks. Only variables with a p-value <0.2 were included in the binomial generalized linear models (GLMs).

A correlation value >0.5 or a variance inflation factor >2-5 was considered as correlation and the variable which was deemed to be less important and/or with the lower impact was removed. Binary regressions were performed using a stepwise method for removing variables that are not associated with the response variable one by one, taking both the p-value of the variable and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) of the model into consideration. The best fitting model was selected by comparing the AIC weights for a set of fitted models. The final model was assessed in comparison with the null model using a likelihood ratio test (R function “anova” with argument test set to “Chisq”). In addition, the individual effect of the variables in the model was tested by Wald tests (R function “Anova” with argument test. statistics set to “Wald”). In order to assess the predictive ability of the model, the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated using the “roc” R function.

Results

Documentation of vaccination

During recent years, the vaccination schedule expanded with the inclusion of new vaccines and/or additional doses, and the layout of YC and HR was gradually adapted. During the review of the vaccination history, we came across different formats and versions of the YC and HR. Major changes in format were introduced with the pneumococcal vaccine (PCV13), the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), the Japanese encephalitis vaccine (JEV) and the second dose of the measles-rubella vaccine (MR). Not all facilities used the latest date version of the HRs or YCs. However, since the pentavalent vaccine was introduced already in 2009/10, it was included in all versions of the YC and the HR inspected in this study. At the CH, the three doses of DTPw-HepB-Hib vaccination were verified in the YC of all participants from Vientiane. Most of these children (65.5%) were vaccinated with all three doses at the Children´s hospital, the others received some or all of the doses at another CH in Vientiane. In Bolikhamxay, the parents of 620 children (73.6%) presented the YC. The vaccination entries in the HR were found for 83.3% of the children and for 56.8%, both sources were available.

Comparison of yellow cards and hospital records

At the Children’s hospital, it was possible to review the HRs of all three doses for 88 (27.6%) participants, and for at least one dose for 155 (48.6%) participants. All vaccination dates matched between the YC and HR. However, for 8 (2.5%) participants, the birth date entry in YC and HR did not match.

In Bolikhamxay, both HR and YC were available from 479 (56.8%) participants. We discovered a number of discrepancies between the two documents.

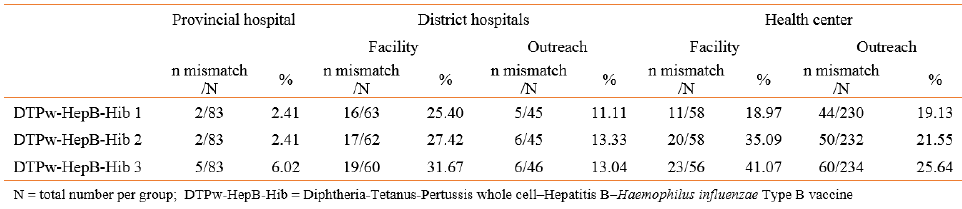

The birth dates of 34 (7.1%) participants differed between YC or HR. From the 479 participants in Bolikhamxay with both HR and YC, 180 (37.6%) had at least one mismatch among the three vaccination date-pairs. Of these 180 participants, 43.3% had a mismatch in the dates for DTPw-HepB-Hib 1 and 62.8% for DTPw-HepB-Hib 3. 17.2% had mismatches for all three date-pairs. The date for DTPw-HepB-Hib 3 in the HR was before the YC in 71 (39.4%) cases while it was later in only 37 (20.6%) of the 180 participants. The proportion of mismatches increased from DTPw-HepB-Hib 1 to 3. At the PH level, only 2.4% to 6.0% of the vaccination dates mismatched from DTPw-HepB-Hib 1 to 3 (Table 14). Table 14. At the DH and HC level, there was a higher proportion of mismatches between vaccination dates at the facility as compared to outreach. The highest proportion of mismatches (41.1%) was found at the health center level among the participants vaccinated directly at the facility. Here, also the largest mean discrepancy between the YC and HR was observed (-9.9 days).

Several other observations were made: In some cases (7.8%) among the 180 participants with both records, either DTPw-HepB-Hib 2 or 3 or both, the HR had the same entry as DTPw-HepB-Hib 1 and/or 2 in YC; many of the mismatches differed by less than 7 days (23.9%) for at least 1 date-pair or even all three date-pairs; for 9.4% of participants all dates in the HR were before the YC; for 7.2%, both the intervals were 4 weeks in the HR but not in the YC and at least one of the dates in the HR was before the one in the YC. On very few occasions, two doses were denoted with the same date or an obvious mistake was made with respect to the recorded year or the day. Because the YC was less likely to be tampered with, the dates in the YC were given priority in case of mismatches. Results 74

Table 14. Comparison between vaccination date pairs from the vaccination books and vaccination cards

Age at vaccination

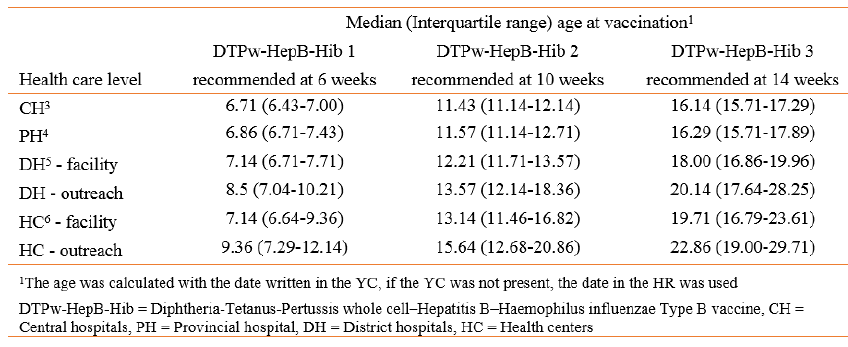

The median age at vaccination with DTP-HepB-Hib 1, 2 and 3 increased at the lower ranked health care facilities (Table 15) and with each dose, e.g. the median age at the first dose was 6.7 weeks at the Central hospital level, but 9.4 weeks at the health center level when participants were vaccinated by outreach services.

The Kaplan-Meier curve shows that at the CH level, 50% of the children were vaccinated at the age of 6.7 weeks with DTPw-HepB-Hib 1 compared to almost 9 weeks at the HC level. For DTPw-HepB-Hib 3, there was a considerable delay at all lower-ranked facilities. At the HC level, 50% vaccination coverage was reached at 23.1 weeks (CI: 22.4-24.4) and considerably fewer children were vaccinated by 24 weeks (6 months) of age compared to CH, PH and DH levels.

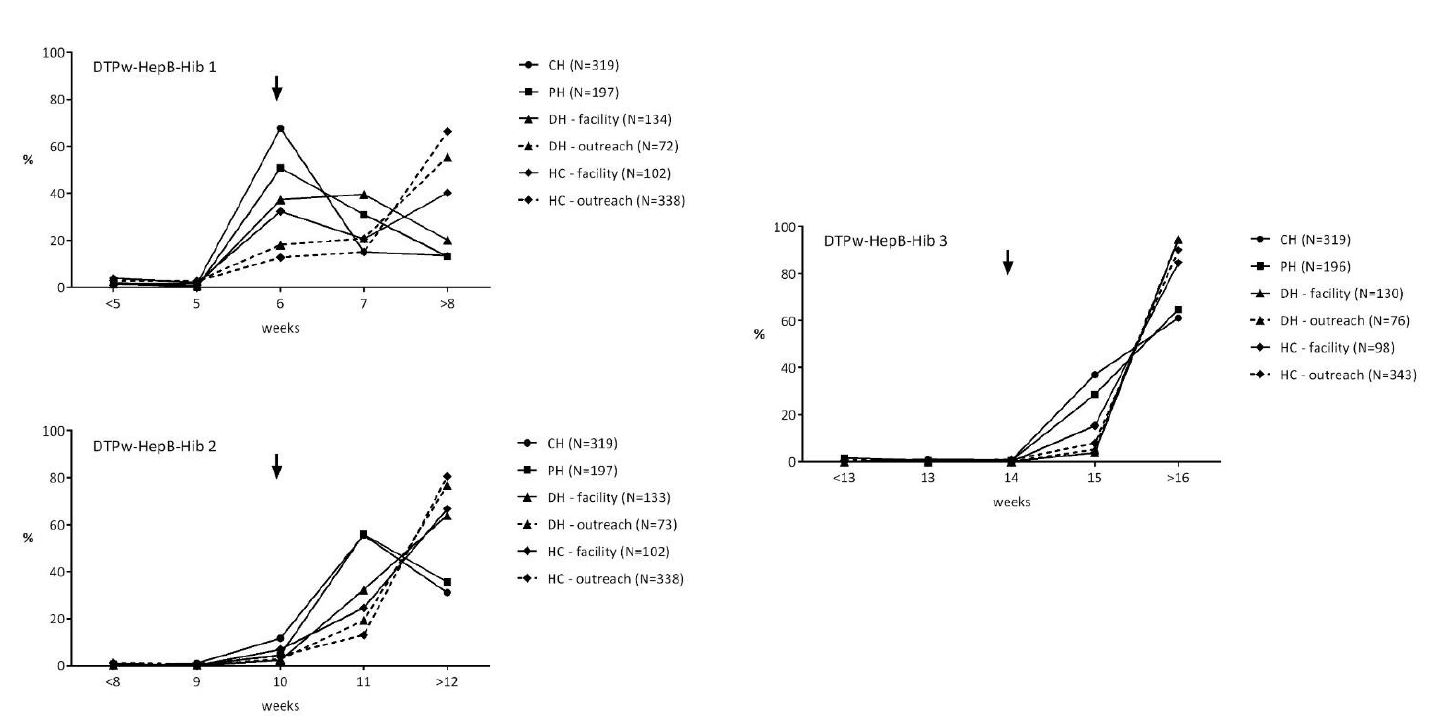

In order to estimate the timeliness of vaccination, the proportion of participants vaccinated at a given age was calculated (Figure 6). The proportion vaccinated at the recommended 6 weeks of age decreased from 67.7% at the CH to 32.4% at the HC, and outreach vaccination was as low as 12.7%. For DTPw-HepB-Hib 2, most of the participants were still vaccinated within a week of delay at the CH and PH. The majority of participants were vaccinated with a delay of 2 or more weeks for DTPw- HepB-Hib 3 at all locations.

Even at the CH level, less than half of the participants had completed the full course of DTPw-HepB-Hib by the time they were 16 weeks old. However, by week 24, more than 90% of the participants at the CH and PH level (94.7% (95% CI [92.2-97.1]) and 92.6% (95% CI [88.8- 96.3]) respectively), as well as participants, vaccinated directly at the DH level (91.5% (95% CI [86.5-96.6])) had received DTPw-HepB-Hib 3. Fewer participants that were vaccinated at the HC level and during DH outreach services were vaccinated with the 3rd dose by 24 weeks of age (58.4% (95%CI [54-62.7], p<0.0001) when compared to the CH.

In order to investigate any association between delayed vaccination (defined as age at DTPw-HepB-Hib 3 >16 weeks) and seroprotection against any of the five vaccine components, bivariate analyses were performed among those children vaccinated at the CH and PH level. Receiving the 3rd (last) dose of the pentavalent vaccination more than 16 weeks after birth was not associated with lower seroprotection in this study.

Figure 6. The proportion of participants vaccinated with DTPw-HepB-Hib 1, 2 and 3 at a given age by health care levels. Arrows indicate recommended week of vaccination. CH = Central hospital level, DH = hospital level, HC = health center level. The age at vaccination was calculated based on the vaccination card, and in case the vaccination card was not available the date in the hospital records was used.

Table 15. Median age at vaccination in weeks according to health care level

The interval between vaccination doses

At the CH level, the median interval between DTPw-HepB-Hib dose 1 and 2 was 4.7 weeks and only somewhat higher for outreach vaccination at the HC and DH level (5.1 and 5.4 weeks respectively). At the CH and PH level, 65-70% were vaccinated within the recommended interval of 4 weeks between doses 1 and 2 and doses 2 and 3. Considerably fewer participants were vaccinated within 4-week intervals in lower ranked facilities. Only very few participants were vaccinated within less than 4 weeks (rates ranging from 0.0% to 4.4%) at any health care level.

For most participants, at least one of the two intervals was longer than 4 weeks (DTPw-HepB-Hib 1 and 2 and DTPw-HepB-Hib 2 and 3).

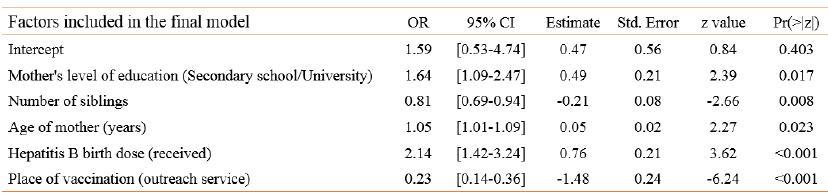

Predictors for timely completion of vaccination with DTPw-HepB-Hib

We used timely completion with DTPw-HepB-Hib 3 at 24 weeks as binary outcome and performed logistic regression analyses to identify predictors in Bolikhamxay province. The bivariate analyses showed that being an older mother with a higher education and a higher household income was more often associated with timely vaccination. Markers of inequity in access to health care (delivery at home, no ANC and no hepatitis B birth dose) all are also predictors of delayed vaccinations. Travel time to health care facilities, vaccination by outreach and not belonging to the Tai-Kadai ethnic group emerged as obstacles to timely vaccination.

In logistic regression analyses all variables associated with the outcome with a p<0.2 were included. However, since “place of birth” and “district” correlated with the “place of vaccination”, these variables were excluded from analyses. “Travel time to the next health care facility” was used as a surrogate for distance and “received ANC” was used as a surrogate for ANC practices in the modeling. The variables “age of participant”, “age of mother”, “number of household members”, “number of siblings” and “travel time to the next health care facility” were included in the logistic model as numeric variables. Several variables remained independently associated with the outcome (Table 16): Participants were more likely to have completed the primary vaccination series by the age of 24 weeks (6 months) if they were not vaccinated by outreach services and if they had received the hepatitis B birth dose. Furthermore, the probability of timely completion increased with age and education of the mother but decreased by number of siblings. The fit of the overall model in comparison to the null model was assessed (p-value < 0.0001, AUC = 77.9%).

Table 16. Binomial generalized linear model showing the factors affecting completion of vaccination by 24 weeks

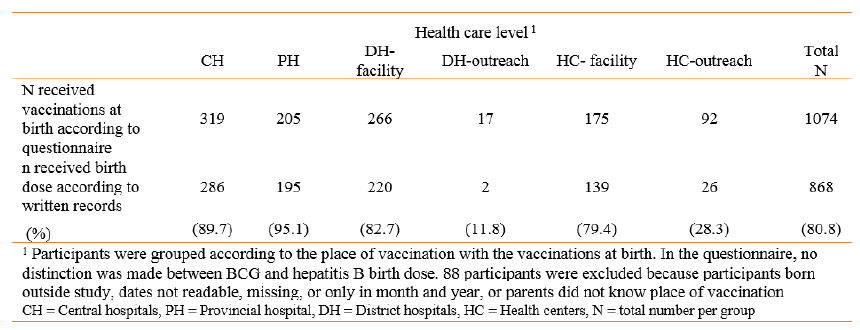

Hepatitis B birth dose and recall by health facility

At the CHs in Vientiane Capital, 89.7% had received the birth dose according to YC or HR compared to 76% in Bolikhamxay (Table 17). All of the parents of participants from Vientiane Capital stated that their children had received the vaccination at birth (BCG and/or hepatitis B birth dose) at the Children’s hospital or another CH. In Bolikhamxay at HC level, only 28.3% of children whose parents remembered that vaccination was given at birth had a record of the hepatitis B birth dose. These participants were almost exclusively born at home.

In Bolikhamxay, both HR and YC were available from 479 participants and from those, 313 (65.3%) participants had a vaccination date for the birth dose. The vaccination dates matched in both HR and YC for 91.7% of these participants.

The hepatitis B birth dose is recommended to be given within 24 h of birth and latest within the first 7 days after birth(Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) on Immunization, 2017). The vast majority of the participants in our study that received the hepatitis B birth dose, did receive it on the day of their birth (93.5%) and only 4.1% did receive it later but within 7 days after the birth date.

Table 17. Numbers of participants that received the hepatitis B birth dose according to their vaccination cards or vaccination records and the level of the health care system

Discussion

Reliable and centralized documentation is important for monitoring vaccination coverage and the quality of immunization programs. When both HR and YC were available, 38% of children had mismatches in at least one of the vaccination date-pairs, and for 63% of those, the date for DTPw-HepB-Hib 3 did not match. At the PH only 2.4% of mismatches were found for the first dose, but in lower ranked health facilities up to 19% of date pairs mismatched. The mismatches increased with each dose (up to 41% at the HC level). There were also 7.1% mismatches in birthdates between the two vaccination records. Mismatches in calendar days, months or years, are indications that dates are not entered simultaneously and at the same session in the YC and HR. Vaccination books are usually assigned to each village and taken along to the village during outreach sessions. When the books or the YC are forgotten, retrospective entry of dates may be common. Vaccination dates may also be entered in the YC in advance as a reminder for the parents, but then vaccination may have taken place at another date. Thus, the importance of written documentation needs to be emphasized at every level of the health system. In particular, the management of hospital vaccination books/records needs to be strengthened, the procedures of record keeping in both the YC and the HR should be reviewed, and additional training of the health care staff is required to improve the reliability of entries.

In bivariate analyses, essentially all indicators of poor access to health services were very specifically associated with delayed completion of DTPw-HepB-Hib vaccinations. While this study included only children who completed vaccination, it could be extrapolated that these are also the risk factors for missing at least the last pentavalent dose. After logistic regression analyses, the lower education level of the mother, not receiving the hepatitis B birth dose as well as vaccination by outreach service, were independently associated with the delayed completion of full vaccination with DTPw-HepB-Hib. Due to the geography and infrastructure of the country, around 30% of the villages are classified as remote and are difficult to access. Outreach services should be conducted in at least four rounds per year; however, in 2016, it was estimated that only 9% of remote villages were visited four times. The education of the mother has also been shown in other studies to be an important driver of timely immunization or timely completion of specific vaccinations. These results indicate that there is a need to further improve access to health services, especially in remote rural areas.

Almost all participants in Vientiane Capital but only two thirds of the participants living in Bolikhamxay had received the hepatitis B birth dose; however, this is probably a considerable overestimation of recipients in the general population, since we only enrolled participants with a full course of pentavalent vaccination. Recent data estimate the coverage for the birth dose in 2017 to be 55% nationwide. Even among children who received all three doses of DTPw-HepB-Hib, only 28.3% had received the hepatitis B birth dose at the health center level in areas covered by outreach. Although the overall number of home births in Lao PDR has decreased from 59% in 2010 to 35% in 2017, these findings are still concerning.

There are several limitations to this study. Those include that the specific place of vaccination (either outreach or on-site) was only available by parents’ recall. Since only children with three doses were included, we cannot determine the number of children who missed one or two doses. Our questionnaire may also not have captured all risk factors for delayed vaccination and our findings may not necessarily be valid for the whole country although it shows a typical pattern.

Conclusion

During the past few years, major progress has been made in Lao PDR in vaccine coverage and seroconversion rates. In this study, we observed a general delay of vaccination with DTPw-HepB-Hib and discrepancies in vaccination records. Vaccination delay was associated with indicators of poor access to health services.

To further improve the child vaccination program and to reliably identify children who missed vaccinations, reasons for the discrepancies and inconsistency in vaccination documents should be investigated and training of health care staff in robust documentation and management of health records should be provided. We suggest including timely completion of vaccination as a quality indicator for the national immunization program in addition to coverage rates and seroconversion rates. These data have been communicated to the Lao Ministry of Health as a policy brief and submitted as a manuscript for publication.